LBJ-Public Health dual degree student Becky Carter’s work with the City of Austin Austin Public Health’s Office of Violence Prevention, Alliance for Safety and Justice, and other community partners has helped and will continue to develop and secure funding for Texas’ first trauma recovery center.

“I wanted to focus on the financial aspect, because if dollars aren’t there, you can’t do the program and do the work that will benefit the community,” said Carter.

Using skills gained from her coursework at the LBJ School, Carter is conducting an initial cost-benefit analysis and developed a program evaluation plan to estimate the potential impact of a trauma recovery center (TRC) on Austin residents affected by violent crimes. Her research will be used to identify next steps for conducting an in-depth cost-benefit analysis, which could be used to advocate for sustainable funding for TRCs across the state in future legislative sessions.

The Trauma Recovery Center Model

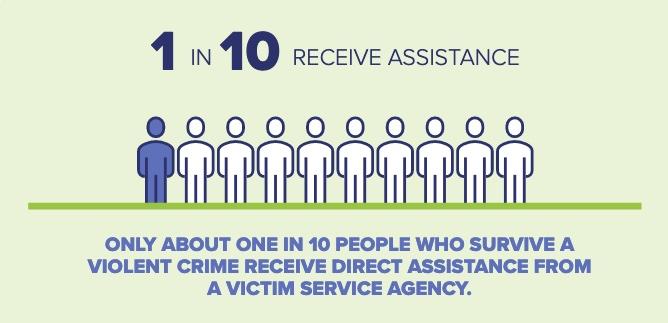

According to a brief released by The National Alliance of Trauma Recovery Centers, four out of ten Texans have been a victim of a crime in the past ten years, but only one in ten victims of violent crime receive victim compensation or support from a victim service agency. The brief also reports that TRCs tend to address the needs of clients “who are largely low-income, from communities of color, and who face significant barriers to accessing other victim services.” Victims of violent crimes like gun violence, sexual assault, and domestic violence often require a complex system of care to heal, both mentally and physically, after the incident.

Support for victims of violent crimes can include access to mental health resources, medication and medical services, housing, and support navigating the legal system. This infographic is pulled from a brief on Texas trauma recovery centers by The National Alliance of Trauma Recovery Centers.

The National Alliance of Trauma Recovery Centers brief states that untreated trauma has costly consequences for the survivor, their family, and the larger community. Unaddressed trauma resulting from violent crime can lead to chronic emotional distress, relationship problems, and self-medicating through increased alcohol or drug use, all of which can lead to problems maintaining employment or housing.

The model behind TRCs recognizes that victims of violent crimes can benefit from wrap-around, survivor-centered services, which can include access to affordable childcare and shelter, food, and support navigating the legal system, in addition to therapy and medication. While there are 39 TRCs established nationwide, there are currently none operating in Texas*.

In 2021, the Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice Austin chapter, part of the Alliance for Safety and Justice, recognized the gap in available services for victims of crime in the Austin area. Around this same time, the City of Austin created the Reimagining Public Safety Taskforce; seeing an opportunity, the Alliance for Safety and Justice (ASJ) approached the City with information about the effectiveness of TRCs.

“The city was looking at innovative ways to improve public safety,” said Terra Tucker, Texas State Director for ASJ. “TRCs were a solution that...fit well into existing and future services.”

Tucker and the team at the Alliance for Safety and Justice (ASJ) approached the City of Austin’s Reimagining Public Safety task force and worked together to provide a set of recommendations in 2021 that included funding an Austin-based TRC. Carter worked with the OVP team, led by Michelle Myles, in 2021 to develop a memo to city council outlining the feasibility of a TRC in Austin. Last summer, ASJ and the OVP used this memo to secure $1 million in funding from the City of Austin to support the creation of the state’s first TRC, to open within the next year.

“It’s awesome to be working with a leader who is truly trying to make Austin more equitable, and I feel proud to be working on a team that’s doing such great work,” said Carter.

Now, Carter is working with the teams at OVP and ASJ to develop a sustainability plan to seek continued funding for the program through grants and governmental support, possibly securing state funding during this year’s legislative session. For this, Carter is using the skills and networks she’s gained from her time at the LBJ School to examine the potential impact of an Austin-based TRC based on data collected from existing centers.

“It's critical to show policy makers and elected officials which policies are worth investing in,” says Tucker. “TRCs are an evidence-based approach that have been proven to make communities safer, improve outcomes, and save lives.”

Developing a Sustainable and Impactful TRC

As part of her master’s thesis, Carter is developing the first cost-benefit analysis of a TRC. While this is a new CBA model, she is looking at it from the perspective of an Austin-based TRC. Carter is using data gathered from cost-effective and programmatic outcome analyses conducted at three established TRCs -- two in California and one in Ohio. Using what she learned in her Public Financial Management course and with the support of her thesis advisor, LBJ School professor Dr. Todd Olmstead, Carter explains that her cost-benefit analysis will take the existing cost-effective data one step further, comparing the cost of a TRC with the dollar value of its outcomes or benefits to victims of violent crime.

“Everything is in monetary terms when doing a cost-benefit analysis, and that hasn’t been done before,” said Carter. “I'm taking a different approach, which will add to the national research but also look at whether a trauma recovery center will be worth it for the Austin community.”

Because the TRC model is relatively new, there is limited peer-reviewed literature with data about cost-benefit analyses for TRCs. However, existing studies show that the three clinics in California and Ohio are cost-effective, which is some of the data Carter is using to develop a preliminary cost-benefit analysis for an Austin-based TRC. Using national data about TRC client demographics and services utilized, Carter has developed six personas of likely clients in the Austin area. Using these personas, Carter can estimate the average cost per client and, subsequently, the direct cost savings needed for a future CBA.

This initial analysis will showcase what data should be collected at Austin’s TRC so in the coming years a thorough CBA can be conducted with data collected from Austin clients. The Alliance of Safety and Justice team can then use this data-backed CBA to support future proposed budget asks and secure more state funding for TRCs.

In addition to making initial steps for a cost-benefit analysis, Carter is also preparing a program evaluation plan that could be used to advocate for sustainable funding for the TRC in future legislative sessions. For this stage of the project, Carter utilized the expertise of faculty and students in her Program Evaluation course last fall, taught by RGK Center professor Dr. Patrick Bixler.

“I wanted to focus on taking this evidence-based program and flipping it and do all the evaluation work proactively before we get to the point where we realize we weren’t collecting the right data and couldn’t make as much of an impact,” said Carter.

In the final project for his course, Dr. Bixler matches student groups with different community organizations to support development of a program evaluation tool, such as logic model or survey, to help organizations gather the correct data and better communicate the impact of their programs. Last fall, Carter shared her work on the trauma recovery center with Dr. Bixler, who was intrigued by the project and saw a unique opportunity for students to learn by working with a program in its early stages.

“The content of Becky’s work experience was so directly aligned to curriculum of what we’re learning in class and that’s such a unique opportunity, the ability to bring her work experiences in real time and build that into the curriculum,” said Dr. Bixler.

Throughout the fall semester, Carter worked with a small group of her classmates to develop a recommended evaluation model for the TRC, beginning with an implementation planning group made up of several stakeholders. The group determined what impact metrics should be collected by the center when it opens to best showcase how the center is producing an impact for the community. As part of her thesis, Carter is also recommending that further economic evaluation be conducted once the TRC programs are up and running.

“When you are proactively thinking about your evaluation design as you’re starting a program, the opportunity to implement an evaluation plan increases exponentially,” Dr. Bixler says. “Being on the front end of this program design and the ability to bring in an evaluation lens is what all programs should do but not what most do.”

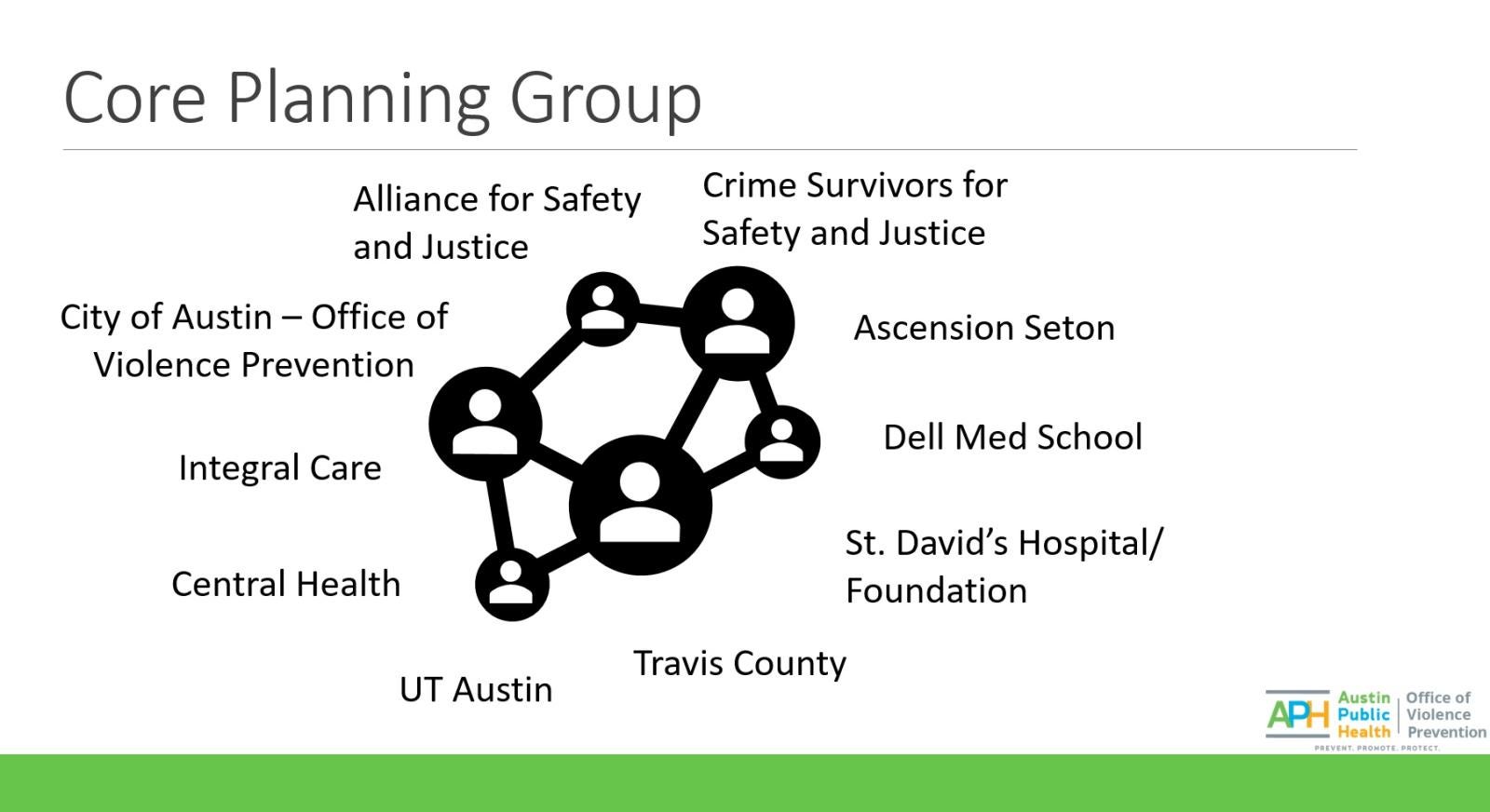

An important aspect of establishing a TRC in Austin is ensuring that the center is integrated into the City’s current violence prevention ecosystem. Throughout the planning process, the OVP has collaborated with healthcare, governmental and nonprofit partners to ensure services aren’t duplicated, funding is shared, and the center is supported by institutions like Austin's only level-one trauma center, Dell Seton.

Organizations from across Austin are collaborating on the development of the city’s first trauma recovery center. This visualization of partnerships is provided by the CoA Office of Violence Prevention.

Carter hopes that this evaluation plan, in tandem with the cost-benefit analysis she conducted for her thesis, will help secure and maintain funding for the TRC during the legislative session. The process has allowed her to utilize skills that she’s learning in her graduate programs at UT Austin, as well as her background in neuroscience.

“I’m really interested in behavioral health work, and I wanted to mix rigorous neuroscience research with something applicable,” said Carter. “This project is combining all the skills I’m learning in impact [at the LBJ School] while still encompassing this underlying behavioral health work.”

Carter, who is herself a victim of a violent crime, hopes that this work developing Texas’ first trauma recovery center will help others navigate the complex process of healing.

“It’s been really awesome getting to do work on this,” Carter said. “It wasn’t there to help me at the time when I needed the services, but it will help people in the future and that’s the whole goal – to help individuals who experience this trauma and show them that healing is possible.”

*There are current efforts underway in Dallas and Houston to develop trauma recovery centers for those communities. Austin was the first city in Texas to secure the minimum seed funding from the City and will be home to the first trauma recovery center in the state.